Robert Lancaster Estate: Intermission About Whiskey Making

I have been discussing

in the last four blogs about the estate inventory of my 5 times

Great-grandfather, Robert Lancaster, who died in 1840 in Shelby County,

Kentucky.

When I discovered that he had two copper stills and

seventy-two barrels of whiskey, I became very curious about whiskey-making. I

began my research on the making of whiskey in the 19th century via the

Internet. I learned some basics from the “Bourbon Whiskey” article on Wikipedia. But I

wanted to learn more.

Two books that I received through inter-library loan were

very helpful:

- The Social History of Bourbon, by Gerald Carson and published by The University Press of Kentucky in 1963, and

- Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey, an American Heritage by Michael R. Veach, and also published by The University Press of Kentucky in 2013.

Because these two books were published by an academic press,

they were well documented.

I was never a drinker of hard spirits, so I didn’t know much

about whiskey. Since reading that an ancestor made whiskey, I wanted to know

more about it. Now after learning about how whiskey was made in his time period,

particularly bourbon whiskey in Kentucky, I want to try some. I have tasted

Scotch whiskey in Scotland. I found that to be very strong and I didn’t care

for it. Perhaps I might like bourbon whiskey better.

What I Learned About

Making Whiskey

This will be the story of small-time whiskey-making. The type made by a farmer, not a distillery.

Whiskey was made from corn, rye, barley malt, yeast, and

limestone water. The farmer grew the

corn and rye. He made the barley malt. The yeast was purchased. The limestone

water came from nearby creek, stream, or spring. Gerald Carlson said in his

book,

“Why limestone water? In distilling, water loaded with calcium, the kind that makes the bluegrass blue, the horses frisky, and perhaps its virtues may even be stretched to explain the beauty of Kentucky women—limestone water teams up perfectly with yeast.”[1]

What they had to purchase or make themselves was the still.

The stills in this time period were made either of wood or copper. Since Robert

Lancaster’s inventory said he had a copper still, I’ll describe what that might

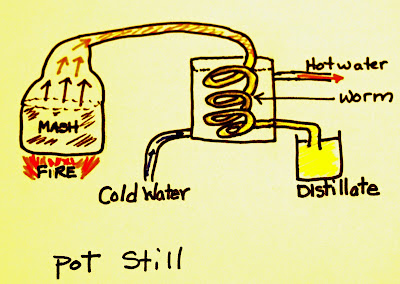

look like. Below you can see a drawing I made to simulate the still.

|

| Still, drawn by Lisa S. Gorrell (c) 2016 |

The copper

still was shaped like a tea kettle with a rounded bottom and topped with a

smaller dome. From this dome was a copper tube that fit into a second part

called the condenser. Inside this condenser the copper tubing, called the worm,

was shaped in a spiral. Cold water entered the condenser to cool down the vapor.

The cooled down vapor was collected as distillate in a tub. The alcohol from this

first distillation still have impurities and was cloudy. The distillate was run

through the still a second time.

Sometimes the still was set up in pairs, so the first

distillate can then go through the process without having to clean out the pot

first. The mash residue in the pot is removed and cooled and used as feed for livestock.

Since Robert had two stills, perhaps his setup was in this “double” fashion. He

also had nearly 200 head of hogs, so the spent mash was likely fed to them.

Gerald Carson also described what a stillhouse might look

like:

“The stillhouse was often no more than a low-roofed shack, with a mud floor and one face open to the weather. The location was usually in a hollow under a hill where clear, cold, limestone water flowed to the worm in a wooden trough...[It] might be located on a creek or branch. A flowing spring was even better because it was necessary to have the water as cold as possible to condense the steam. If the water was warmer than in the range of fifty-six to sixty degrees, the distiller had to suspend operations or move to another location.”[2]

The mash was made first by grinding the corn. They likely

worked with a bushel at a time. A bushel of shelled corn weighed 56 pounds.[3]

A helper, most likely one of Robert’s slaves, mashed the corn with water and a

portion rye in large mash tubs. Some of the hot mash from a previous distillation

was added to the mash to scald it, making it into a consistency of mush. Then

it was let to cool overnight to “sour” it. To that mash, barley malt was stirred

into it. This helped the grain turn into sugar. After more stirring, yeast was

added, now creating carbon dioxide as the yeast eats the sugar. This liquid now

stays in the fermenter tub for up to seventy-two hours. When the temperature

was about 75 degrees (tested by the distiller’s hand), it was ready to distill.

Today, distillers use thermometers and stills have gauges.

A day’s work might create ten gallons; a week’s worth two

barrels. If Robert Lancaster had 72 barrels of whiskey, that equated into about

36 weeks of work if the barrels were of fresh whiskey, and of any that was

aging. It would be impossible to determine if any were aging.

Aging was what made good Kentucky whiskey what is well-known

today as bourbon. Kentucky whiskey is whiskey that is aged in newly charred barrels. Scotch

whiskey casks are re-used and not charred. Canadian whiskey packages are

charred but not new. The whiskey aged in charred barrels is what gives us

bourbon. Gerald Carson described what happens in the barrels as it ages:

“When the temperature rises, the whiskey expands into the char. When it falls, the whiskey contracts. A ripening occurs. The liquid is gentled. An oily feeling and a strong ‘bead,’ visible around the edge of a glass, develop.”[4]

However, what Robert Lancaster made was just whiskey. There

has not been found any reference to the name bourbon before 1855. He may not

have even charred his barrels. We cannot tell from the inventory. But it is

possible he know of the qualities charred barrels made for his whiskey. He may

also have known that aging improved the whiskey.

[1]

Gerald Carson, The Social History of

Bourbon, The University Press of

Kentucky, 1963, p. 43.

[2] Gerald

Carson, The Social History of Bourbon, The University Press of Kentucky, 1963, p. 43.

[3] “Bushel,”

Wikipedia.org : accessed 16 October

2016).

[4] Gerald

Carson, The Social History of Bourbon, The University Press of Kentucky, 1963, p. 41.

Copyright © 2016 by Lisa Suzanne Gorrell, Mam-ma's Southern Family

Comments

Post a Comment

All comments on this blog will be previewed by the author to prevent spammers and unkind visitors to the site. The blog is open to other-than-just family members particularly those interested in family history and genealogy.