Robert Lancaster’s Estate: Wheat farming

I have been working on probated estates of farmers who died

in mid-century 1800. One of the items that was in the estate inventories was a “wheat

fan.”[1]

In Robert Lancaster’s estate in 1840, there was a wheat fan

that was valued at $5.00 and sold for $6.87 in the estate sale. I imagined a

wheat fan as something made from wheat stalks shaped in a fan to be used when

the weather was a bit warm to help cool you down.

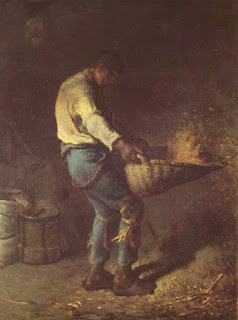

A search for a definition of a wheat fan brought up photos of

winnowing baskets. These large baskets were used to separate the wheat grain

from its chaff by tossing the wheat into the air and allowing the chaff to blow

away in the wind.

Later, winnowing machines were invented and were in use by

the time of Robert’s death. It is quite possible that he owned a machine that

had either been purchased or hand-made. He must have grown some wheat as he had

40 bushels worth $20 at the time of his death.

Although we cannot know for sure how Robert raised and

harvested his wheat crop, I have found written accounts of growing and

harvesting wheat. From the History of

Pocahontas County, which is in West Virginia, an account told of what was

needed to plant the wheat.[2]

“Ploughed in with the bull tongue or shovel plow, brushed over by a crab brush or thorn sapling, and in many instances simply laboriously dug in with a hoe, it was a precarious crop, owing to freezing out, blight or rust.”

Robert Lancaster had 14 Plows and 2 large harrows listed in

his inventory that were valued at $34 and in the sale, these were identified individually.

Bull tongue, shovel, and Cary plows were sold during the sale.

|

| Carey Plow |

Another account of wheat planting was written by John Jay Janney, who wrote about his early

life farming in Virginia.

“We plowed for next year's wheat crop, and when the ground was ready for sowing we hauled all the manure from the barn yard and the hog pen ...We would take a bag and tie the string to one corner so we could hang it about the neck...and carry...about a bushel of wheat in it. We would catch up handfuls and sow them broadcast having first marked out the field into ‘lands’ of a proper width. A little practice enabled one to sow very evenly. We then dragged a heavy harrow over it.”[3]

Because of the number of plows Robert owned, it was likely

he used them in the planting of the wheat.

Harvesting was done with scythes. Five scythes were sold in

the sale. The wheat was held by one hand and cut with the other. The handful of

wheat would be tied together into sheaves and then stacked to dry. Once dried

they were placed on the ground and trod by horses.

|

| licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Germany |

Janney continued his tale.

“We would take the sheaves into the barn, take off or loosed the bands, and lay a ring of sheaves four feet or four sheaves wide all around the floor. We laid the first one flat on the floor, the next one with the heads upon the butts of the first and so on all around the floor. We thus had a ring of sheaves about four feet wide, with the heads of the wheat only showing, and a vacant space in the middle of the floor, of about twenty feet in diameter.

“We then put four horses, two abreast, walking around on the wheat, against the way the wheat pointed. After the horses had walked around sufficiently, two of us would each take a pitchfork, one on each side of the wheat, and turn it over. This we would repeat until the grain was all out of the straw, which was then raked off and stored as feed for the cows and steers during the winter.”[4]Now the wheat needed to be separated from the chaff. It would be tossed into the air and clean in a coarse sieve. Then the wheat would be placed into the wheat fan. It would be run through twice. Here is an image of a machine made in the 1850's. It was run by a hand crank that created the fan to separate the wheat from the chaff.

|

| From American Farmer, 1854, p 225 |

Janney wrote that the farmer rarely sold the wheat. They took it to the mill for credit for it “at the rate of sixty pounds to the bushel and when they wanted flour, they got for every sixty pounds of wheat, forty pounds of flour and about fifteen pounds of bran.”[5]

Robert’s wheat would also be used in the making of the whiskey he had on his premises. In all, I imagined it was hard work and most likely his slaves performed this work. Four men and two boys were listed in the inventory.

For a photo of an old wheat fan, check out this blog post with photos.

[1] Shelby

County, Kentucky, Probate, Bk 14, p. 63-68, 1840, Robert Lancaster, digital

images, FamilySearch (http://familysearch.org : 22 Sep 2016); citing FHL film

259254, item 3.

[2]

William T. Price, Historical Sketches of

Pocahontas County, West Virginia, Price Brothers, Publishers, Marlinton,

WV, 1901.

[3] “Early

19th-Century Wheat Farming Near Waterford,” History

of Loudoun County, Virginia (http://www.loudounhistory.org/history/agriculture-mills-and-wheat.htm

: accessed 29 Oct 2016).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

Copyright © 2016 by Lisa Suzanne Gorrell, Mam-ma's Southern Family

Comments

Post a Comment

All comments on this blog will be previewed by the author to prevent spammers and unkind visitors to the site. The blog is open to other-than-just family members particularly those interested in family history and genealogy.